Aluminum occupies a paradoxical position within the context of sustainability. Light, strong, and endlessly recyclable, it’s an enabler of decarbonization found in everything from packaging and products to solar panel frames and lightweight EV components. Yet its production can be energy intensive and carbon heavy, especially when extracted from its raw form, or ore, called bauxite. Norwegian aluminum giant Hydro, a premier renewable energy company, continues to address the industry’s systemic issues through radical creativity and a shift in priority with their most audacious attempt yet – the R100 project unveiled at Capsule Plaza during Milan Design Week 2025.

With renewed focus and uncompromising resolution, Hydro examines the environmental cost of transportation, attempting to further reduce their total carbon footprint as Hydro CIRCAL 100R – the world’s first 100% post-consumer aluminum developed by the brand – is transformed from scrap material to artful objects by designers Sabine Marcelis, Keiji Takeuchi, Cecilie Manz, Daniel Rybakken, and Stefan Diez all within a self-imposed limit of a 100 km radius from locally sourced material.

A Radical Experiment in Hyper Local Urban Mining

Hydro CIRCAL 100R boasts a record-low carbon footprint under 0.5 kg CO₂e per kilo, but what if that’s not enough given the current climate crisis? How might local production slash additional emissions in the oft-overlooked, startling metric that results from transportation through global supply chains.

“The idea of containing the whole project within a 100 km radius came to me just days after opening the 100R exhibition,” says art director, designer, and Hydro collaborator Lars Beller Fjetland who has been spearheading the initiatives. “Could we really source, melt, extrude, machine, and finish everything in one tight cluster,” Fjetland asks. “We don’t do these projects because they’re easy. We do them because they’re hard.”

Blissfully unaware of any limits by radius, the designers received an open-ended creative brief free from constraints with only a few non-negotiable rules: each object must be mono-material and each construct must be fully recyclable. Atypical of creative assignments, Hydro’s approach encouraged open dialogue and instilled a sense of trust in the process ultimately fostering conditions ideal for ingenious fabrications.

“My process of curation is very much related to personal chemistry… I work with designers that have a consistent expression and stay true to their design language and process. This is more easily achieved by working with individuals rather than larger studios, as the objects become an extension of their unique and beautiful minds,” Fjetland adds. “The interesting thing is that the pressure to come up with something original, innovative and beautiful primarily comes from the designers themselves. We don’t need to add to that pressure, but rather facilitate and turn it into a constructive force.”

One Metal, Five Objects, Endless Stories

What started as some 52 tons of locally sourced aluminum scrap from defunct greenhouses and decommissioned lampposts became a unique collection of products varying from decorative objects to home furnishings and even furniture components, each revealing a different facet of aluminum – both technically and emotionally.

Sabine Marcelis’ Orbit Light treats extrusion not as structure but as a vessel for light. Its asymmetrical, large-scale profile was so technically challenging that Hydro’s engineers initially declared it near impossible – until a handful of determined die technicians found a way to make the molten aluminum flow through the extrusion die in just the right way. Activated by its dimmer, light appears to escape the figurative event horizon with incredible depth leaving shadows behind.

A derivative from the Norwegian word for “profile,” Keiji Takeuchi’s Profil outdoor chair celebrates modularity and precision as each extruded component snaps together with near-invisible seams somehow steering away from sterility. Initially conceived as a single-profile system, execution demanded a scalable, modular approach in which some parts share silhouettes. This versatility breeds an expandable landscape – a family of benches and stackable chairs to be realized, lounge or high-back, with or without armrests.

Simple pieces transcend the pragmatic for something more poetic like Cecilie Manz’ Rør hardware, imbued with unbridled meaning through their incredible potential. Aptly named – its moniker meaning “tube” in both Norwegian and Danish – reimagines the humble form, embracing simple imperfections that playfully contrast industrial perfection.

Entitled Fields, Daniel Rybakken’s work is pure abstraction as cylinders and planes invite the eye to see a forest in a stack of extruded rods. The romantic narrative is conjured by the perfect balance of proportion, contrast, and finish. Free from commercial constraints, the designer is able to fully experiment with recycled aluminum and create something felt as much as seen.

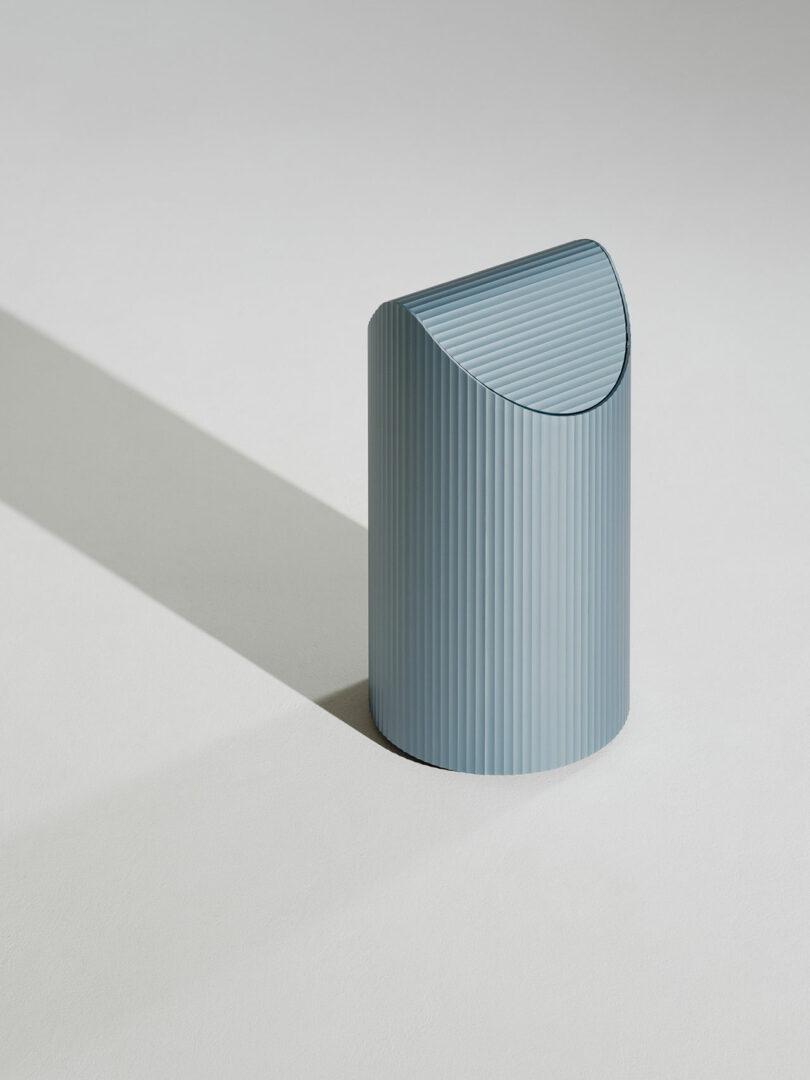

And Stefan Diez’ Boss recycling bin reframes waste management as an intentional, visible ritual. Its minimalist form – including the feet, bag holders, and pivoting axis of the lids – is manufactured from the same aluminum that once held up streetlights. What’s more, the clever design enables systemized production reinforcing a consistent and resource-efficient design approach for something surprisingly whimsical.

Scalability with Limitless Possibility

The final numbers are compelling: a 90% cut in transportation emissions, mono-material pieces with fully traceable recycled content, and a powerful proof of concept for local manufacturing networks. In the end, the only pivot came when select large-scale extrusion demanded a bigger press, forcing Hydro to split production into two separate 100 km clusters. Even so, each object remained hyper-local, with no single component exceeding the boundary.

Design is critical in advancing material innovation and making the circular economy a reality. As the climate clock ticks louder, the design world’s material choices matter more than ever. A chair or lamp isn’t just an aesthetic gesture – it’s a tiny part of a colossal resource economy that will require international commitments to global infrastructure and participation. The sooner designers embrace, nay demand, circular principles, the faster creative communities can move the needle.

In practice, this means choosing appropriate materials with the lowest possible carbon footprint and ensuring they’re recyclable. It also means creating products that can be easily taken apart so their materials can be separated and reused at the end of their life cycle. It is essential for the protection and preservation of Earth’s finite resources.

“The project is a testament to the fact that no company or person can create a circular economy or solve other complex challenges that the world is facing today in isolation,” says Jacob Nielsen Director Communication at Hydro Extrusions. “We are dependent on each other, and when we partner with others, great things can happen.”

To learn more about Hydro and their initiatives visit r-100.no.

Photography by Einar Aslaksen.