Exploring newly released estimates of current policy warming

Posted on 19 November 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

It’s the COP time of the year: the 30th Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC. In addition to countless delegates trekking down to Brazil, this also means the release of a number of high-profile reports approximately timed to the COP to maximize their impact.

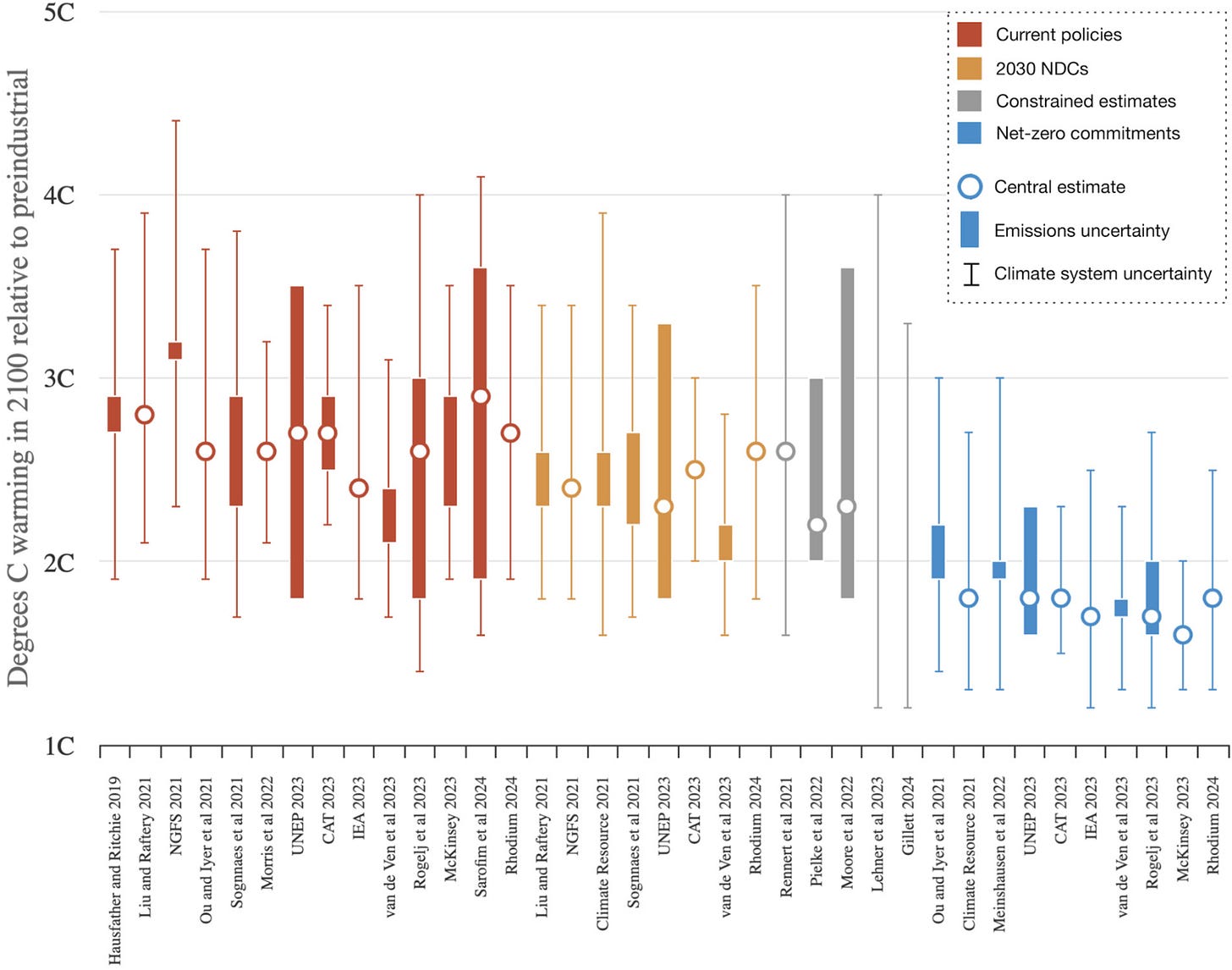

This year we have three new analyses that explore how much warming might be in store for us under current policies in place today as well as if countries meet their near-term nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement and their long-term net zero targets. The new analyses include updates to the high profile annually re-occurring estimates from the UNEP Emissions Gap Report, the IEA’s World Energy Outlook, and Climate Action Tracker (CAT).

In addition, three other studies were released this year on current policy warming outcomes from Rhodium, Wood MacKenzie, and Jiang et al., 2025.

Central estimates from these studies vary from 2.9C by 2100 (IEA CPS) to 2.4C (Jiang et al 2025), with Rhodium at 2.8C, UNEP, CAT, and Wood MacKenzie all at 2.6C, and IEA STEPS at 2.5C (up a tad from 2.4C in its 2024 report). However, these central estimates can obscur the large uncertainty in the climate system response due to climate sensitivity and carbon cycle feedbacks; its possible that current policy warming could be as high as 4C if we roll 6s on the proverbial climate dice.

These 2025 updates provide a useful follow-on from the summary of the literature included in my Dialogues on Climate Change paper published at the start of the year.

One interesting development this year was the IEA’s decision to revived its “Current Policy Scenario” (CPS) that was discontinued after 2020 in response to pressure from the Trump administration, as Carbon Brief explains:

This pathway is named the “current policies scenario” (CPS), which assumes that governments abandon their planned policies, leaving only those that are already set in legislation.

If the world followed this path, then global temperatures would reach 2.9C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 and would be “set to keep rising from there”, the IEA says.

The CPS was part of the annual outlook until 2020, when the IEA said that it was “difficult to imagine” such a pathway “prevailing in today’s circumstances”.

It has been resurrected following heavy pressure from the US, which is a major funder of the IEA that accounts for 14% of the agency’s budget.

Confusingly, both CPS and the “Stated Policies Scenario” (STEPS) represent versions of current policies. STEPS excludes commitments that are not codified in sectoral level targets or regulations, and reflects a world of very modest expansion of current policies that generally results in higher emissions than scenarios where countries meet their Paris Agreement Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). For this reason, I’ve shown the range between the two as the current policy emissions uncertainty in the IEA report.

The general concurrence of 2100 warming estimates across different groups suggests that the world is heading toward less warming than was expected 15 years ago, when most estimates were closer to 3.5C or 4C. How much of this decline is driven by earlier scenarios being unrealistic vs progress on technology and policy is an interesting debate that I’m planning to address in a future article, so watch this space!