A newly discovered comet will soon be gracing our evening sky.

On Sept. 10, Vladimir Bezugly of Dnipro, Ukraine was examining online images of a low-resolution public website showing images obtained during Sept. 5-9 with the Solar Wind Anisotropies (SWAN) camera on the Solar and Heliospheric Observer (SOHO) spacecraft. That’s when he discovered a moving object, resembling a bright blob, close the sun. The blob turned out to be a comet. A bright comet.

In fact, as Bezugly later noted: “In my memory, this is one of the brightest comet discoveries ever made on SWAN imagery,” adding, “the 20th official SWAN comet so far.” Since Bezugly’s first sighting, many other amateurs — primarily in the Southern Hemisphere — have viewed it. The comet has since received a formal IAU designation on Sept. 15 as Comet C/2025 R2 (SWAN).

Astronomers rely on magnitude to determine brightness. Magnitude is a numerical scale used in astronomy to measure the apparent brightness of celestial objects, where lower numbers indicate brighter objects, and higher numbers indicate dimmer objects. The brightest stars are magnitude 0 or +1, while the limit for naked-eye visibility under a dark, non-polluted sky is considered to be magnitude +6.5.

A consensus of the most recent observations of comet SWAN indicated a magnitude of +7, which places it just out of the reach of naked-eye visibility under dark, moonless skies. Good binoculars, however, can readily bring it into view.

The typical description of the comet by those using binoculars and small telescopes is a small, condensed head or coma with a thin, faint tail extending for roughly 2 degrees.

Nikon Prostaff P3 8×42 binoculars

The Nikon Prostaff P3 8×42 binoculars offer up great optics at a modest price, allowing you to focus on constellations with ease at 8x magnification. They are even reinforced with strong fiberglass and have a shockproof design making them resistant to accidental drops and bumps. Why not check out more of their features on our full Nikon Prostaff P3 8×42 binoculars review?

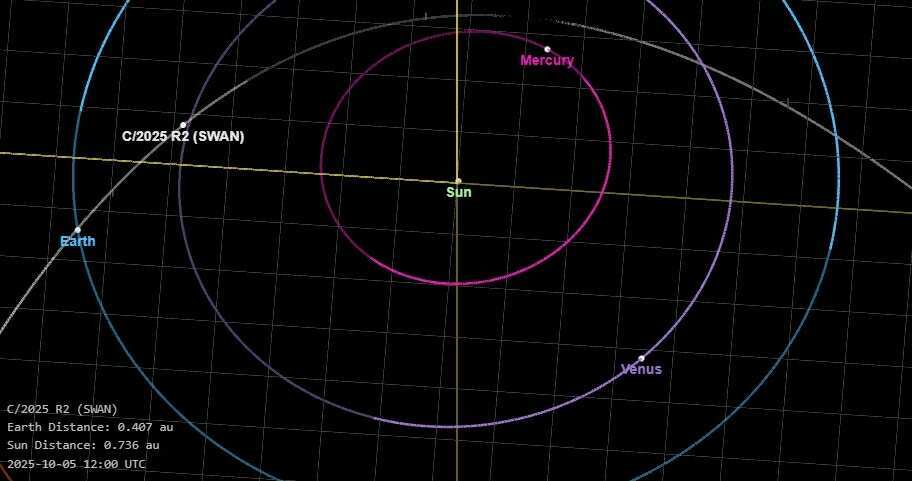

An orbit based on 60 different observed positions between Sept. 12 and 14, 2025 has been calculated by Syuichi Nakano of the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. He finds that the comet passed perihelion — its closest point to the sun — on Sept. 12 at a distance of 46.74 million miles (75.20 million km).

While it is now moving away from the sun, it is currently approaching Earth. It will come closest to us (perigee) on Oct. 21 when it will be 25.10 million miles (40.38 million km) away. Based on its orbital eccentricity of 0.996015, the time it takes for comet SWAN to make one complete circuit around the sun is estimated to be on the order of roughly 1,400 years.

How bright?

A number of different predictions have been made regarding the brightness Comet SWAN as it passes closest to Earth during the third week of October. To date, brightness forecasts issued by Japanese comet expert Seiichi Yoshida and Dutch comet expert Gideon Van Buitenen indicate that the comet will peak somewhere between magnitude +6 and +7, probably placing it right on the cusp of naked-eye visibility, but certainly within reach of good binoculars or small telescopes.

Daniel W.E. Green at the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams, suggests that comet SWAN will hover near magnitude of +6, from Oct. 2 to 20, perhaps becoming a few tenths of a magnitude brighter for a few days around Oct. 12, meaning it might become faintly visible with the unaided eye.

Where to find it and viewing prospects

Right now, as we noted earlier, comet SWAN has been primarily visible from the Southern Hemisphere; it’s been too close to the sun to be easily visible north of the equator. But that will gradually change by the end of this month, as the comet takes a more northerly path. It will slowly climb higher in the southwest sky during the first ten days of October, reaching an altitude of 12 degrees above the horizon at the end of evening twilight (approximately 90 minutes after sunset).

Your clenched fist is equal to roughly 10 degrees when held at arm’s length. By Oct. 28, the comet’s altitude will have climbed to 30 degrees (“three fists”) above the south-southwest horizon by nightfall and by Oct. 25 it will stand halfway up in the southern sky when twilight ends, and not set until after midnight.

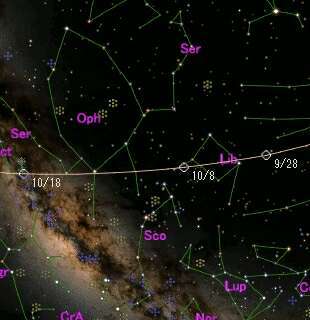

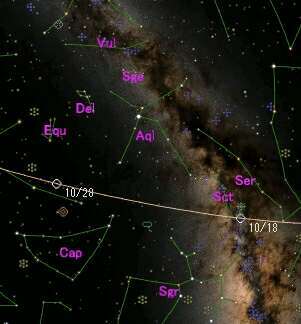

During October, comet SWAN will move along a path taking it across the constellations of Libra, Scorpius, Ophiuchus, Serpens, Scutum, Sagittarius, Aquila and Aquarius.

As is the case with another comet we have recently discussed — comet Lemmon — sighting comet SWAN may prove to be rather difficult for locations that are plagued by light pollution. Remember, you’re not looking for a sharp star-like object, but rather something which is spreading its light out over a comparatively large area.

Like comet Lemmon, comet SWAN does not appear to be a dusty comet but is primarily composed of gas. Such comets appear fainter than comets composed primarily of dust (which is a far better reflector of sunlight) and glow with a bluish-white hue. The gas is activated by the ultraviolet rays of the sun, making the comet glow in much the same way that black light causes phosphorescent paint to light up.

So, most who ultimately locate Comet SWAN in their binoculars or telescopes will likely describe it as a nearly circular cloud, appearing noticeably brighter and more condensed near the center. Some might also detect its faint tail appearing as a bit of a thin, narrow appendage extending out from the comet’s coma; sort of like an “apple on a stick,” but hardly the kind of tail exhibited by other larger and brighter comets.

Meteor shower? (NOT!)

One other attribute that has been widely promoted on social media about comet SWAN is the possibility that it might cause a meteor shower sometime between October 4 to 6. The reason that this potential has been suggested is that in diagrams showing the comet’s orbit relative to the orbits of the inner planets, it appears that comet SWAN’s orbit intersects the orbit of the Earth right around Oct. 5.

The assumption is that if there is any meteoric material that has been shed by the comet on previous trips around the sun, that there is a chance that the Earth will encounter it around the time it intersects the orbit of the comet.

An intriguing theory, but it is not likely to happen.

The reason is that the orbits of Earth and comet SWAN will not intersect on Oct. 5. What is transpiring is that both objects are traveling on curtate orbits. When looking at the orbital paths from a perspective high above, it certainly appears that the orbits interact with each other.

But in reality, according to my calculations, at the Oct. 5 point of our orbit, the comet orbit — and any possible cosmic debris that is traveling along it, will travel far above our orbit and will miss us by some 4.4 million miles (7 million km). That is far too wide a gap between the two orbits to hope for any type of semblance of significant meteor activity.

Besides, the best chance to encounter any meteoroids shed by comet SWAN would be behind it. But Earth arrives at the Oct. 5 point, ahead of it, 16 days before the comet itself passes by. And we’ve already noted that comet SWAN is mostly a gaseous comet and not a dusty comet. So, it is not likely shedding very much material along its path around the sun. Thus, even if we were to encounter the comet orbit directly, there seems little chance we’d encounter very much comet debris to produce many celestial streaks.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.