This computer-simulated image shows a supermassive black hole at the core of a galaxy. The black region in the center represents the black hole’s event horizon, beyond which no light can escape the massive object’s gravitational grip. The black hole’s powerful gravity distorts space around it like a funhouse mirror. Light from background stars is stretched and smeared as it skims by the black hole.

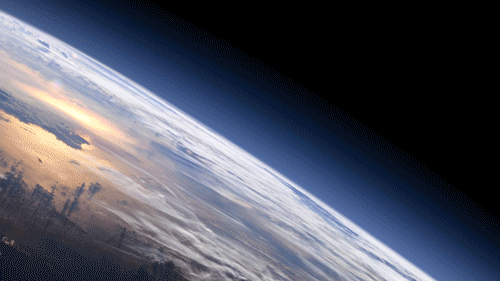

You might wonder — if this Tumblr post is about invisible things, what’s with all the pictures? Even though we can’t see these things with our eyes or even our telescopes, we can still learn about them by studying how they affect their surroundings. Then, we can use what we know to make visualizations that represent our understanding.

When you think of the invisible, you might first picture something fantastical like a magic Ring or Wonder Woman’s airplane, but invisible things surround us every day. Read on to learn about seven of our favorite invisible things in the universe!

1. Black Holes

ALT

ALTThis animation illustrates what happens when an unlucky star strays too close to a monster black hole. Gravitational forces create intense tides that break the star apart into a stream of gas. The trailing part of the stream escapes the system, while the leading part swings back around, surrounding the black hole with a disk of debris. A powerful jet can also form. This cataclysmic phenomenon is called a tidal disruption event.

You know ‘em, and we love ‘em. Black holes are balls of matter packed so tight that their gravity allows nothing — not even light — to escape. Most black holes form when heavy stars collapse under their own weight, crushing their mass to a theoretical singular point of infinite density.

Although they don’t reflect or emit light, we know black holes exist because they influence the environment around them — like tugging on star orbits. Black holes distort space-time, warping the path light travels through, so scientists can also identify black holes by noticing tiny changes in star brightness or position.

2. Dark Matter

ALT

ALTA simulation of dark matter forming large-scale structure due to gravity.

What do you call something that doesn’t interact with light, has a gravitational pull, and outnumbers all the visible stuff in the universe by five times? Scientists went with “dark matter,” and they think it’s the backbone of our universe’s large-scale structure. We don’t know what dark matter is — we just know it’s nothing we already understand.

We know about dark matter because of its gravitational effects on galaxies and galaxy clusters — observations of how they move tell us there must be something there that we can’t see. Like black holes, we can also see light bend as dark matter’s mass warps space-time.

3. Dark Energy

ALT

ALTAnimation showing a graph of the universe’s expansion over time. While cosmic expansion slowed following the end of inflation, it began picking up the pace around 5 billion years ago. Scientists still aren’t sure why.

No one knows what dark energy is either — just that it’s pushing our universe to expand faster and faster. Some potential theories include an ever-present energy, a defect in the universe’s fabric, or a flaw in our understanding of gravity.

Scientists previously thought that all the universe’s mass would gravitationally attract, slowing its expansion over time. But when they noticed distant galaxies moving away from us faster than expected, researchers knew something was beating gravity on cosmic scales. After further investigation, scientists found traces of dark energy’s influence everywhere — from large-scale structure to the background radiation that permeates the universe.

4. Gravitational Waves

ALT

ALTTwo black holes orbit each other and generate space-time ripples called gravitational waves in this animation.

Like the ripples in a pond, the most extreme events in the universe — such as black hole mergers — send waves through the fabric of space-time. All moving masses can create gravitational waves, but they are usually so small and weak that we can only detect those caused by massive collisions. Even then they only cause infinitesimal changes in space-time by the time they reach us. Scientists use lasers, like the ground-based LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) to detect this precise change. They also watch pulsar timing, like cosmic clocks, to catch tiny timing differences caused by gravitational waves.

This animation shows gamma rays (magenta), the most energetic form of light, and elusive particles called neutrinos (gray) formed in the jet of an active galaxy far, far away. The emission traveled for about 4 billion years before reaching Earth. On Sept. 22, 2017, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole detected the arrival of a single high-energy neutrino. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope showed that the source was a black-hole-powered galaxy named TXS 0506+056, which at the time of the detection was producing the strongest gamma-ray activity Fermi had seen from it in a decade of observations.

5. Neutrinos

This animation shows gamma rays (magenta), the most energetic form of light, and elusive particles called neutrinos (gray) formed in the jet of an active galaxy far, far away. The emission traveled for about 4 billion years before reaching Earth. On Sept. 22, 2017, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole detected the arrival of a single high-energy neutrino. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope showed that the source was a black-hole-powered galaxy named TXS 0506+056, which at the time of the detection was producing the strongest gamma-ray activity Fermi had seen from it in a decade of observations.

Because only gravity and the weak force affect neutrinos, they don’t easily interact with other matter — hundreds of trillions of these tiny, uncharged particles pass through you every second! Neutrinos come from unstable atom decay all around us, from nuclear reactions in the Sun to exploding stars, black holes, and even bananas.

Scientists theoretically predicted neutrinos, but we know they actually exist because, like black holes, they sometimes influence their surroundings. The National Science Foundation’s IceCube Neutrino Observatory detects when neutrinos interact with other subatomic particles in ice via the weak force.

6. Cosmic Rays

ALT

ALTThis animation illustrates cosmic ray particles striking Earth’s atmosphere and creating showers of particles.

Every day, trillions of cosmic rays pelt Earth’s atmosphere, careening in at nearly light-speed — mostly from outside our solar system. Magnetic fields knock these tiny charged particles around space until we can hardly tell where they came from, but we think high energy events like supernovae can accelerate them. Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field protect us from cosmic rays, meaning few actually make it to the ground.

Though we don’t see the cosmic rays that make it to the ground, they tamper with equipment, showing up as radiation or as “bright” dots that come and go between pictures on some digital cameras. Cosmic rays can harm astronauts in space, so there are plenty of precautions to protect and monitor them.

7. (Most) Electromagnetic Radiation

ALT

ALTThe electromagnetic spectrum is the name we use when we talk about different types of light as a group. The parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, arranged from highest to lowest energy are: gamma rays, X-rays, ultraviolet light, visible light, infrared light, microwaves, and radio waves. All the parts of the electromagnetic spectrum are the same thing — radiation. Radiation is made up of a stream of photons — particles without mass that move in a wave pattern all at the same speed, the speed of light. Each photon contains a certain amount of energy.

The light that we see is a small slice of the electromagnetic spectrum, which spans many wavelengths. We frequently use different wavelengths of light — from radios to airport security scanners and telescopes.

Visible light makes it possible for many of us to perceive the universe every day, but this range of light is just 0.0035 percent of the entire spectrum. With this in mind, it seems that we live in a universe that’s more invisible than not! NASA missions like NASA’s Fermi, James Webb, and Nancy Grace Roman space telescopes will continue to uncloak the cosmos and answer some of science’s most mysterious questions.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!