Even when architect Tyler Kobick was in daycare he was already a skilled creative. Taking cues from his mother, who painted watercolors, he loved to tap into his imagination and draw animals of all shapes and sizes.

Kobick was raised in Ohio, in a house next to the bluffs where the Wisconsin Glacier ends, 30 miles south of Lake Erie. The land was a refuge, where an icicle kingdom formed in the winter and large boulders doubled as hideouts in the summer. “From small nooks to expansive spaces, the cliffs turned into my workshop to make forts and experiment with making,” he says. “Scavenged pieces of wood became my medium from a very early age.”

Tyler Kobick \\\ Photo: Courtesy of Design Draw Build

Kobick was more interested in natural terrain than typical school sports. He built a rock climbing wall in his basement and organized trips to outdoor locales. When he was 14 he also began an apprenticeship with a master stone mason, and by age 16 he started his own construction company.

A licensed architect and contractor, Kobick founded Design Draw Build in 2010, and traveled throughout the United States, Canada, and El Salvador for commissions. Now permanently based in Oakland, California, the firm specializes in a range of projects, from adaptive reuse to multi-family housing, always embracing the material culture of a place.

Kobick’s favorite time is when the brainstorming transitions into the actual pitch. “It is a vulnerable and empathetic process, one where you adjust to the client’s initial reactions,” he notes. “Actively molding the idea to meet a position that allows both parties to move forward is a wildly exciting experience.”

Today, Tyler Kobick joins us for Friday Five!

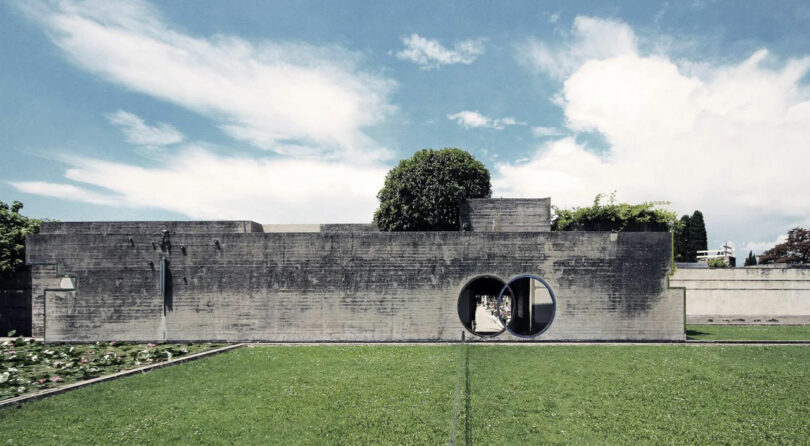

Photo: Trevor Patt

1. Brion Cemetery near Treviso, Italy

Designed by Carlos Scarpa, my favorite twentieth-century architect, the Brion Cemetery in San Vito d’Altivole near Treviso, Italy, is a modernist masterpiece and Mayan temple of the 20th century. It is a monument to the permanence of everyday change that expresses the fluidity of architecture and construction. It speaks to the vulnerability of the day to day making process from brain to build and 30 years of work by an architect and craftsman I so strongly believe in.

Photo: Tyler Kobick

2. Shallow Atmospheric Depth (SAD)

I love patterns and drawing things that allow the eye to enter a thing to some degree and drift or meander back out of it. I have great regard for creative works that inspire immersive imagination that is less of a trance and more of a dance.

Photo: Courtesy of South Louisiana Blackpot Festival and Cookoff

3. Gumbos of the World

Like good chowders in New England or Pho in Vietnam, music that expresses the regional story of a place and has been shaped by different influences profoundly inspires me. A specific output rooted in time and place is a quality I seek in food, wine, music, art and architecture. Historic vernacular has evolved, modern, momentary and fleeting.

Photo: Yanit Mehta

4. Critical Regionalism

First coined by Kenneth Frampton in 1981, “critical regionalism” is a theory that trusts the phenomenology of texture over eye-based aesthetics. It’s a theory that seeks a bridge between vernacular, place-based ideas and global modern ideas. It embraces ‘the gumbo’ of a place without being overly nostalgic for the origin of those stories and ideas and seeks new stories that make ‘regionalism’ modern – a current, evolving form.

Photo: John Bogna

5. Trowel

The trowel is a participant in the puzzle of pulling a stone out of the ground and piecing it with another. As an extension of the hand, it allows you to pick something up, put it down, see how it transforms, molding to its new surroundings, forcing mini compromises and revealing surprises.It is a plastic medium that nestles into its surroundings.

Works by Tyler Kobick and Design Draw Build:

Radiant Hills House \\\ Photo: Marcus Edwards

Radiant Hills House

The Radiant Hills House, tucked away in the serene Oakland Hills, embodies the harmonious fusion of the curated reuse of salvaged materials, the original home’s mid-century design, and mindfully-modern functionality. Letting the materials guide the vision, this project reflects my personal design philosophy. As architect-owner, the renovation and additions to this 1949 home have transformed it into a vibrant living space serving as my family home, a home office, and a small multi-family neighborhood daycare. Revived with a critical regionalist approach, the home is at its core a response to place and the local environment, with a number of colorful twists and turns along the way. For me, the Radiant Hills House is more than a home – it is a personal sanctuary and an experimental space dedicated to the ‘design-build’ process. The home reflects my vision and lifestyle, integrating elements from my architectural practice and personal life. It stands as a prototype for DDB’s future work, continually evolving with my deepening understanding of the site and advances in building science.

Radiant Hills House \\\ Photo: Marcus Edwards

Radiant Hills House \\\ Photo: Marcus Edwards

Coda House \\\ Photo: Marcus Edwards

Coda House

After inheriting a childhood home, the owners wanted to make it their own – updating the 1950s ranch house to a warmer, modern layout. A new primary suite wing was added, wrapping around a new outdoor dining patio next to the existing pool. The suite features expansive cathedral ceilings and large windows and doors opening into the back yard. The front entry was redesigned, blending the mid-century ranch home with the modern style of the renovation.

Garden View ADU \\\ Photo: Yanit Mehta

Garden View ADU

Nestled in a sunny hillside – this airy, bright detached ADU is built on a family home in Oakland. The incredibly hands-on and exuberant owners who actively led the build are downsizing and the matriarch will be aging in place. I designed a contemporary ADU suiting all of the owner’s dwelling needs with an integrated loft office, bedroom, kitchen, and bath. The double-height property is the epitome of sustainable intergenerational living. The build process meticulously integrates a modern green design – adding rooftop solar array, passive solar shading devices, a highly efficient building envelope and rainscreen system, energy-efficient fixtures and appliances, EV charging station, an energy-efficient heat pump HVAC system, and sustainably sourcing materials whenever possible. The indoor-outdoor living space is adorned with a splendid accordion glass

Photo: Fireplace in Concrete House \\\ Collective Quarterly

Fireplace in Concrete House

I built and designed this large fireplace in a house made almost entirely from local stone and concrete in the Mad River Valley of Vermont nearly 25 years ago with local, natural boulders rising out of the floor and becoming a man-made object shaped from the plasticity of concrete. The fireplace plays with the contrast of variable shaped materials interacting with each other and seeks a transition from ledge to wall similar to a European castle wall rising from the rock outcropping on a hill. The fireplace embodies my belief in the adaptability of material to the design and encourages the viewer to understand the making process in the aesthetic of the outcome.

Educational Spaces: El Salvador to East Los Angeles \\\ Image: Courtesy of Design Draw Build

Educational Spaces: El Salvador to East Los Angeles

My interest in an education system and a school is about the plurality of public space. Both these works seek a comprehensive architectural link between resource use and production, land development, and education spaces that fortify people’s understanding of place in the ecosystem of the environmental and human community. The Amun Shea project in El Salvador was a school I founded in 2005 and eventually became part of my Master’s thesis at Dalhousie University. It uses an educational campus to define the edge of town and to catalyse local knowledge to stem the migration of rural people to the city. Interior spaces, exteriors, and building techniques for the school and land planning follow a language of overlap between urban street form and the plaza/commons corner.

In similar themes of communal resiliency and an evolution of over 15 years of work, my firm’s Agualta STEAM Engine was designed for sustainable futures with similar aspirations to Amun Shea fifteen years before. Recently a winner of AIA California’s Architecture at Zero competition, Agualta STEAM Engine is a mass timber structure that creates an oasis of scholastic and climate resilience on the Griffith Middle School campus. With over 15,000 displaced Angelenos today following the firestorms, the design harnesses the iconography of water towers as a symbol of sustainable futures for the historically underserved East Los Angeles community and creates a space for re-vocationalism in the education system for a major working class area of the city.