The Xenomorphs are arguably the greatest movie monsters of all time; a petrifying bundle of invasive parasites, weaponized jaws, and dangerously acidic blood.

When director Ridley Scott teamed up with artist HR Giger for the original “Alien”, they bioengineered their creature for maximum terror, and Xenomorph XX121 (to give its official Weyland-Yutani designation) has proved remarkably durable ever since.

So, with this so-called “perfect organism” about to be released into a whole new habitat in eagerly anticipated TV show “Alien: Earth“, we decided to get the lowdown on its terrifying biology. We called zoologist Paolo Viscardi, keeper of natural history at the National Museum of Ireland, to find out if any of the creature’s infamous characteristics might be plausible in real life — stopping short of the magical “Prometheus” black goo, which makes no logical sense at all.

Parasite lost

They may be apex predators capable of surviving in the most hostile environments, but Xenomorphs still need to take advantage of unwitting hosts — human or otherwise — to further the family line.

Paolo Viscardi says: “Parasites tend not to kill their host. They might make them sick, but generally speaking, their function is to work alongside the host so that they can get what they need, without causing a host so much stress that it dies. Things like the Alien [and some species of wasp] are parasitoids because they actually kill their host. [Synthetic Andy actually uses the term to describe the Facehuggers in “Alien: Romulus”.]

“The number of parasites out there is massive, and frankly, they’re incredible things that do all sorts of weird stuff. One of my favorites is the tongue louse, which usually comes in through the gills of the host fish (something like a red snapper), eats the tongue, and then takes its place. It clamps itself onto the stub of the tongue and then feeds on what the fish is feeding on, so it has literally replaced the thing that it destroyed.”

The circle of life

You know the ridiculously complicated Xenomorph life cycle by now… A queen lays the eggs, Facehuggers hatch and impregnate a host, Chestbursters emerge (killing the host in the process) and quickly grow up to become Drones.

Paolo says: “There are life cycles way more complex than that! The lancet liver fluke is a great example. When an ant gets infected with its larval stages, the lancet liver fluke switches something in the ant’s brain so that, instead of going back to their nest at night, they climb to the top of a blade of grass and hold on with their mandibles. Then, in the morning, they come back down again and carry on doing their normal ant duties.

“The reason for this is that cows graze more frequently at dusk and at night, meaning they can’t see that there are weird things on their food, and they eat the liver fluke. The cows then poop out cysts, which get eaten by snails, and their faeces get eaten by ants. All of these things go back into keeping the chain continually moving along, and each one of these different hosts provides another opportunity for the liver flukes to disperse.”

Bigmouth strikes again

Because when you’re hunting down space truckers, colonial marines, hardened criminals and even naïve kids, an extra set of jaws can be a very useful weapon.

Paolo says: “There are quite a few different species that make use of a jaw with multiple components that allow it to reach out way further. There are loads of teleost fish that have strongly invertible jaws, and they work in a very interesting way because they basically vacuum in water by rapidly extending their mouths. Dragonfly nymphs have a lower section of their mandibles that kind of unhinges, shoots forward, grabs stuff, and comes back in again, so very much like the Alien!”

Crunchy on the outside

Members of Xenomorph Species XX121 are famous for wearing their skeletal structures for the whole world to see.

Paolo says: “Exoskeletons are pretty versatile, but one of the issues with them is that they can’t grow like an endoskeleton. We grow by adding extra material to our internal skeletons, but it’s much harder to grow an exoskeleton. Generally, you have to grow it in one big go, shed your old one, and then inflate the new one and let it harden.

“But you’re very, very vulnerable when you’re shedding your exoskeleton. It also leaves you in a position where you’ve got no structural support anymore — the exoskeleton is what provides that extra support — and that’s one of the reasons why the size of organisms that have an exoskeleton seems to be limited. Outside of an aquatic environment, it’s very hard to shed an exoskeleton and not collapse under your own weight, though in space that wouldn’t be an issue.”

They grow up so fast

Aliens neatly sidestep that awkward adolescent phase by growing from cat-sized Chestburster to human-dwarfing Drone in a matter of hours.

Paolo says: “You’d be surprised how quickly something can grow when it sheds its old exoskeleton, so this is not completely unthinkable. The new exoskeleton will often be folded and ridged and crumpled up inside the old one to take up a much smaller volume. Then, when the old exoskeleton is shed, the new one, which is soft, gets inflated using haemolymph [the arthropod equivalent of blood] or whatever. That process can happen quite rapidly.

“There could be quite a lot of empty space inside the new exoskeleton, and that is useful because it allows you more room to grow before you come to your next moulting phase. But the animal would also be pretty feeble at this stage — if this happened in a very short period of time, the muscle growth wouldn’t be able to keep up with the expansion of the exoskeleton.”

“Romulus” also introduced a new stage in Xenomorph development, revealing that the Chestburster-Drone growth spurt takes place inside a very icky cocoon.

Paolo says: “Cocoons are what you need for metamorphosis, which is pretty much complete liquidation of the whole body in order to grow a new form which can often be completely different to the old one. Having a cocoon stage makes perfect sense when you’ve got a significant change in morphology, but the process would take a while.”

Heat vision

The Xenomorph has always proved remarkably adept at stalking its prey without visible eyes, and “Romulus” confirmed that Facehuggers lock onto potential hosts via a potent combination of sound and heat signatures.

Paolo says: “There are loads of things that effectively use thermal imaging to find prey or figure out where they’re going. Mosquitoes can detect infrared effectively — it’s still a form of seeing, but they’re using infrared so they’re able to detect warm-blooded things.”

Vacuum packed

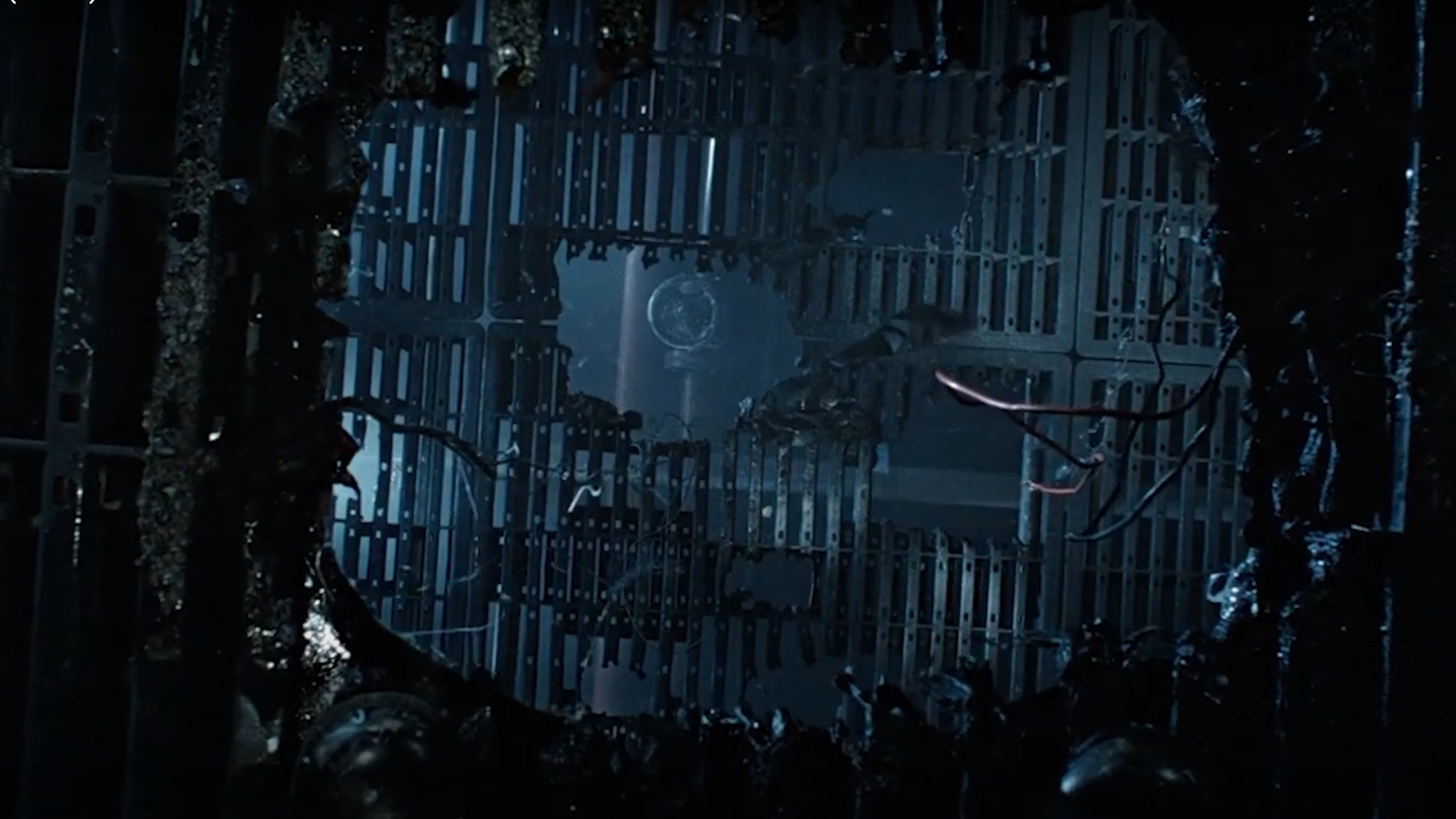

The Xenomorph had already proved robust enough to emerge from the mediocrity of the “Alien v Predator” movies unscathed. Then “Romulus” proved they can also survive for decades in the cold vacuum of space.

Paolo says: “There are certainly tardigrades which have been taken up into the vacuum and been fine. I’d say the bigger you are, the harder it is, but it’s not impossible — and if it can happen with one animal, it can probably happen with something else.

“I think this would depend a bit on whether the Xenomorphs are cold-blooded or warm-blooded. [This isn’t entirely clear from the movies, though in ‘Aliens’, they don’t appear to ‘show up on infrared at all’.] If you cool the environment, a cold-blooded species will slow down and stop, but that doesn’t mean it won’t start up again as soon as it’s warmed up. Actually, this can be really beneficial, because it means the metabolic processes operate much more slowly, and they effectively go into stasis. Warm-blooded species tend to have to maintain certain metabolic processes in order to survive, so in some ways being cold-blooded would make a lot more sense for the Alien.”

Burn baby burn

Species XX121 has one final pièce de resistance, an adaptation so ingenious that shooting them with pulse rifles tends to be really bad for your health. Yes, the Xenomorph circulatory system is filled with a lethal, extremely melty cocktail of sulphuric and hydrofluoric acid.

Paolo says: “It makes sense for digestive juices to be composed of acid, that’s fair enough, but I don’t think it would be particularly good at transporting oxygen, and nutrients would just be completely dissolved. So the Alien’s highly acidic blood is a bit weird, but there are examples of very strong acids, like stomach acid, being made in nature.”

In search of perfection

Android “brothers” Ash and Rook share a disconcerting admiration for the Xenomorph, describing the creature as a “perfect organism”. Hyperbole?

Paolo says: “I would say everything is a perfect organism, I think that’s a better way of looking at it. Everything has adapted to its environment and is the best it can be at surviving in that environment at any given point of time — otherwise it wouldn’t be here. It’s a case of something being perfect for a particular thing, and that’s actually the whole point about evolution — everything is perfect and nothing is perfect.”

“Alien: Earth” is on Hulu and FX in the US from Tuesday, August 12, and Disney+ in the UK from Wednesday, August 13. Check out our How to Watch Alien: Earth guide for more info.