The three chimneys of the 3,617-megawatt (MW) plant that powers Lamma and much of Hong Kong have spewed coal dust onto the island’s inhabitants since the early 1980s. But Lamma’s residents speak about the facility with a mixture of familiarity and indifference, sometimes pride. Like the ageing regulars who prop up the shorefront bars, the power station has blended in with the background, ignored and all but forgotten.

Nick Lovatt, a well-known local character who moved to Lamma six years after the plant started firing in 1988, says he no longer takes any notice of the structure that looms over where he sells secondhand books off Yuen Shue Wan Main Street, which is packed with mainland tourists on weekends. “It’s been around for as long as anyone can remember, and doesn’t seem to have killed anyone,” he told Eco-Business.

“We are sort of proud of it. If we are on the ferry and see the three chimneys, we know we haven’t sailed to Cheung Chau [Lamma’s neighbouring island] by mistake. I only wish that we could plug our decks into it for parties,” says the former journalist and radio DJ.

Nick Lovatt, known locally as “Nick the Book”, points to the Lamma Power Station chimneys opposite where he sells secondhand books. Lovatt moved to Lamma in 1988, six years after the plant was built. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Running perpendicular to the 50-hectare facility is a sandy tree-lined strip known as Power Station Beach, which is a popular spot for revellers, campers and dog-walkers on an island known for its eclectic mix of creatives, musicians, and journalists from all over the world. Other than the Indigenous Hakka fisherfolk, there are about 60 different nationalities living on Lamma, and most have chosen the island’s laid-back, unconventional lifestyle over the chaotic bustle of Hong Kong Island or Kowloon.

Mark Counsell, a digital product designer who lived on Lamma in the 1990s, likens living with the power station to living with tinnitus, a hearing condition characterised by a constant ringing sound that he suffers from. “When you first get it, you think it will drive you mad. But one day you find that you’ve tuned it out without realising it,” he said.

Power Station Beach by night. The beach is a popular place for swimming, dog-walking and parties. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Power Station Beach by day. Beach-goers tend to position their towels away from the power station so that it isn’t in view, says former resident Mark Counsell. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Richard Lord, a British journalist who has lived on Lamma for more than 20 years, acknowledged that people living on the island never complain about the power station. Apart from the chimneys, the power station is quite well hidden from view, so there is an “out-of-sight-out-of-mind element to it,” he said.

But the power station is a lot more than a curiosity on the horizon. It is a cultural symbol that represents the island’s maverick character, adding a certain quirkiness that locals feel helps the place stand out from picturesque Lantau or New Territories. “Lamma is not just a pretty face but a weird one,” said Lord.

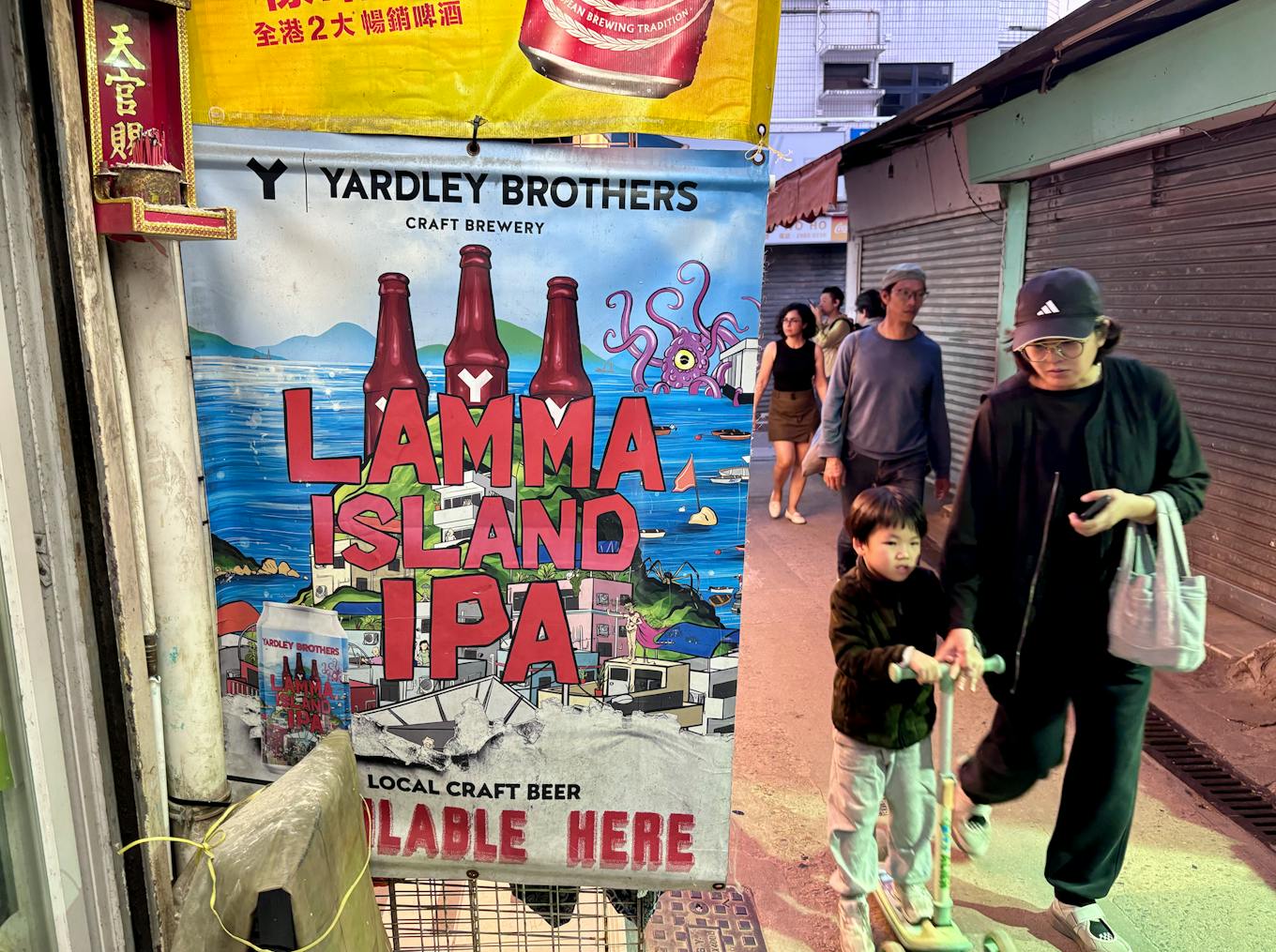

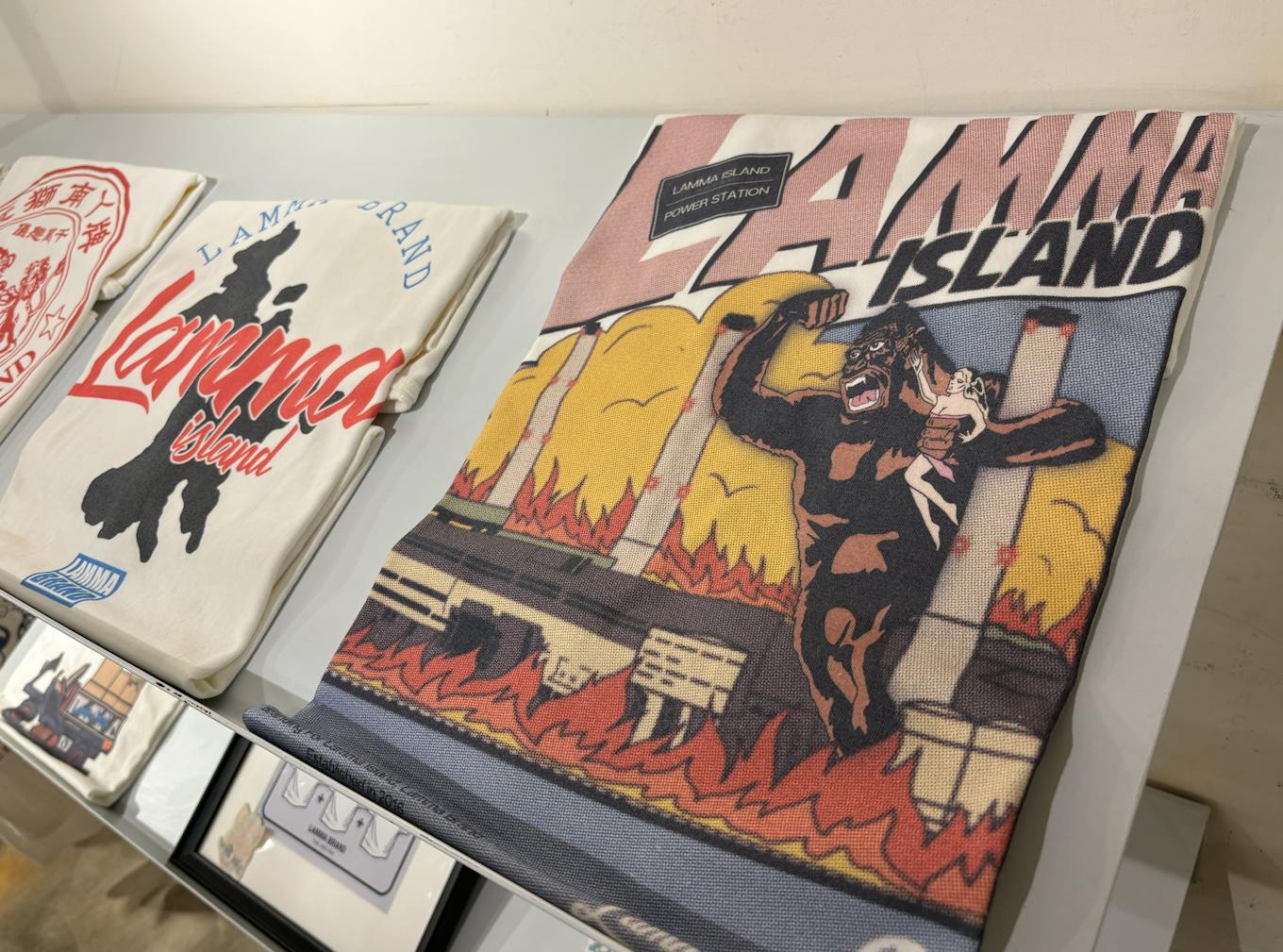

Lamma-based companies even use the plant’s chimneys as a selling point. The 150-metre smokestacks feature on t-shirts and baseball caps in the Lamma Brand clothing store, on the back of pizza boxes at Lamma Express pizzeria and on the labels of cans of the local craft beer.

Lamma Power Station is part of the logo for Lamma Express, a local pizzeria. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Branding for Yardley Brothers’ Lamma Island IPA beer features the three chimneys of Lamma Power Station depicted as beer bottles. Yardley Brothers is a Lamma-based craft brewery started by Luke and Duncan Yardley in 2016. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Lamma Brand t-shirts featuring the island’s coal-fired power station besieged by fictional gorilla-like monster King Kong. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Lamma Brand power station t-shirt on Yuen Shue Wan Main Street. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Most locals Eco-Business spoke to defended the plant – as if, perhaps, defending their decision to live so close to it.

Michelle Kwok, an electrical engineer who sells artisanal coffee on a stall near the pier on weekends, contends that the harmful substances that extrude from the chimneys are “minimal”, because the plant is well designed and maintained, and meets local pollution standards.

“If you stand behind an old car, inhaling its fumes is more harmful to you than the power station’s fumes,” she said, adding that the chimneys tend to blow the smoke northwards, towards Hong Kong island. “Even though there are dioxins in it, if you eat charred pork every day, that is probably more carcinogenic than Lamma Power Station.”

Eco-Business visited store owners in Yun Shue Wan, the main village next to where the power station lies in Po Lo Tsui, to ask if they were concerned about pollution from the plant. The owner of a joss sticks store who has lived on Lamma for 50 years said that he has not suffered from respiratory issues and has never heard of any complaints.

A chef working at the local pizzeria said the furnaces only burn at night, and the only trace of pollution he has noticed is coal dust that occasionally collects on his window sill. A fruit juice vendor said she trusts the government to put the right pollution controls in place, and points out that Hongkong Electric, the power company that runs the plant, even does tours of the facility for tourists.

Maurine Gerrard, an English national who runs a jewelry stall on the island, said she might have objected to the power station being built if it hadn’t been there when she arrived in 1996. “It was here when I got here and I accepted it for what it was. Like the wind and the rain, it’s just there. It doesn’t affect us in any way. I don’t think we get any pollution from it,” she said.

Alan Wheelband has lived in Tai Peng, a hillside village 12 minutes walk from Lamma Power Station, for more than 25 years. He once helped to maintain the chimneys flues for Hongkong Electric and said most of Hong Kong’s pollution comes from shipping and factories across the border, not Lamma Power Station. Besides, less smoke billows from the chimneys these days, he said.

“I used to be able to ‘taste’ it. It was like putting a battery on your tongue, a bit metallic. Nowadays, not so much.”

A coal stock pile is visible behind the plant’s chimney stacks. Conversions to natural gas have meant that emissions from the plant have started to fall. Image: Louis Ng / Beach-Searcher

Lamma Power Station seen from the hillside village of Tai Peng, where Alan Wheelband has lived for the last 25 years. He says he used to be able to “taste” the emissions from the plant. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business

Wheelband argues that the plant now burns more natural gas than coal, and is less polluting. But this is not entirely true. Interviews with residents also reveal that other misperceptions of the impact of the coal plant’s emissions persist.

Lamma Power Station has gradually shifted from coal to natural gas since 2006, but coal remains its biggest fuel source. New gas-fired units were added in 2010, 2020 and 2022. But the power station generates 2,000 MW of power from coal, 1,060 MW from gas and 555 MW of oil. A single megawatt of power is produced from solar panels that were installed on the roof of the facility 15 years ago.

Hong Kong’s biggest climate pollution sources

Measured in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per 100 years:

1. Hong Kong International Airport: 13.16 million

2. Lamma Power Station: 9.72 million

3. Black Point gas-fired power plant: 8.44 million

4. Castle Peak coal-fired power plant: 7.80 million

5. International shipping: 3.44 million

6. Domestic shipping: 2.97 million

7. West New Territories landfill: 2.10 million

8. South East New Territories landfill: 1.56 million

Source: Climatetrace.org

Hongkong Electric told Eco-Business that its new gas-fired units produce half the greenhouse gas emissions of the coal-fired units. More gas units are planned for 2029, and the plant will have shifted away from coal entirely by 2035 as part of the company’s plan to be net zero by 2050.

According to Hongkong Electric’s latest sustainability report, levels of sulphur dioxide from the plant increased last year, while nitrogen dioxide, mercury and carbon dioxide dropped slightly. The company told Eco-Business that pollution from the plant has not exceeded Hong Kong environmental regulations or emissions standards, and its gas-fired units have pollution filters that have cut nitrogen oxide emissions by 90 per cent.

For now though, Lamma Power Station is still the second largest source of climate pollution in Hong Kong after the airport, according to greenhouse gas emissions tracker Climate Trace (see box). But emissions from the plant will have to fall in line with the government’s emission cap reductions for the electricity sector that will take effect from 2030, announced in June.

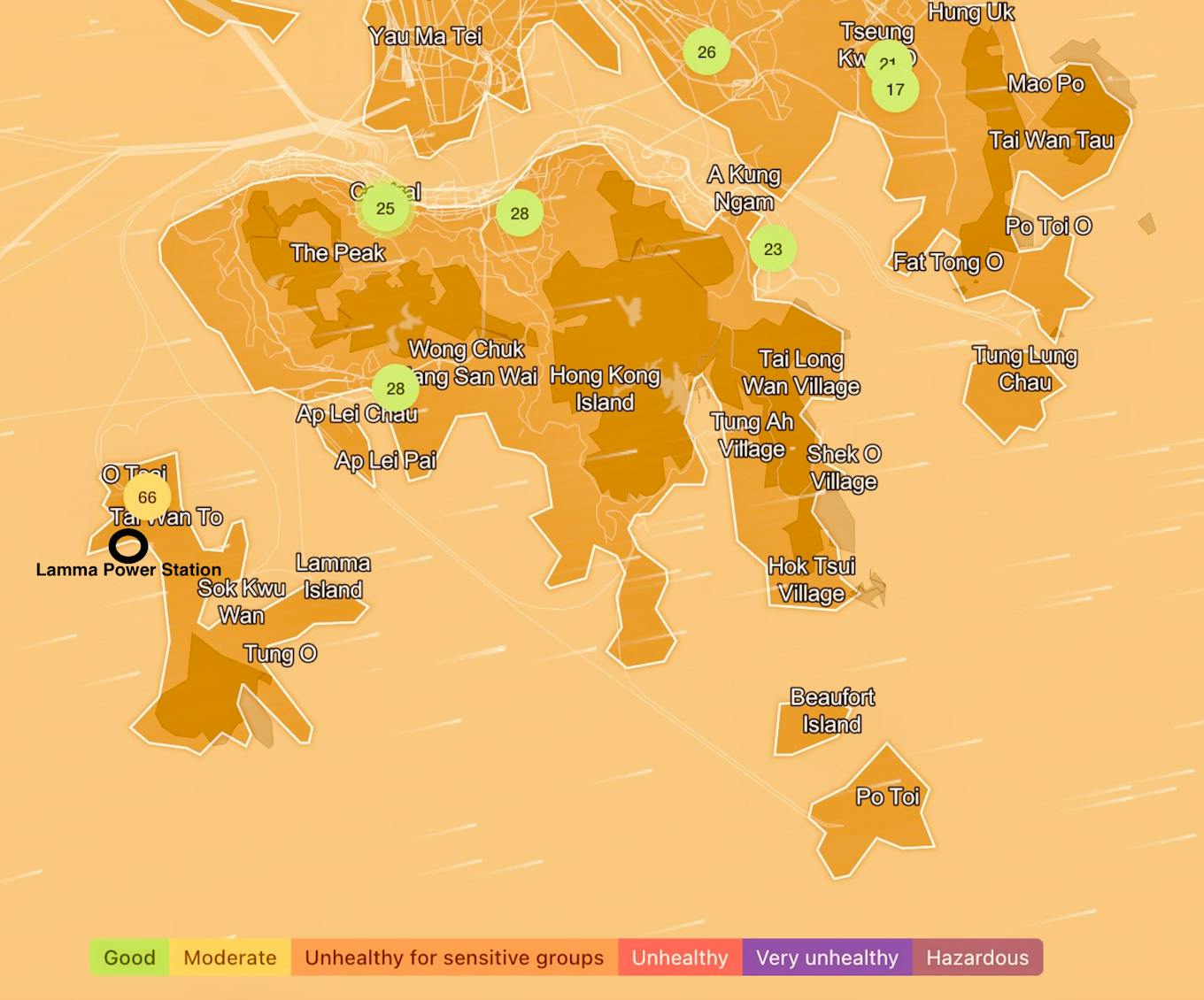

As for particulate pollution, the concentration of PM2.5, or the tiny particles small enough to be inhaled deep into the lungs that cause health problems, on Lamma Island is generally comparable with – and not lower than, as some residents have insisted – that on Hong Kong island and Kowloon, according to data from air pollution monitor IQAir,

Air pollution in the Hong Kong region on 14 August 2025, according to data from IQAir. Lamma Island’s air quality index score of 66 equals 17 miligrammes of particulate pollution per cubic metre (mg/m³), which exceeds the World Health Organisation’s safe threshold of 10 mg/m³. Source: IQAir air quality map

Public buses, lorries and ferries are more to blame for PM2.5 pollution where most Hongkongers live – which is more than three times above guidelines set by World Health Organisation, according to a 2024 study by Hong Kong Clean Air Network. However the non-profit’s chief executive Patrick Fung said there is no way of accurately assessing how polluting Lamma Power Station is, as the government has not positioned any of its 18 air quality monitors there; all are concentrated on Hong Kong island and Kowloon.

Data from IQAir is based on projections rather than observational data, and so is less reliable, Fung added.

If particulate pollution levels on Lamma were more widely known, perhaps the cost of living would not be as high, Fung suggests. Though Lamma rental prices are lower cheaper than on Hong Kong island, they might be significantly lower if living next to the plant was factored into the equation, he said.

The Hongkonger, who once lived on Lamma, said that residents feel powerless to do anything about the coal plant, which is partly why they put up with it. No one has ever protested against the facility – not that that would be much of an option now, in a political climate of declining democratic freedoms.

The only person Eco-Business spoke to who criticised the power plant was a man from Kowloon who lived in Pak Kok Kau Tsuen in North Lamma as a child. He was visiting his family farm plot over the weekend. He said the plant’s biggest impact was on the water supply.

The pipes that channel electricity from Lamma to Hong Kong island had contaminated natural springs that used to produce drinkable water, said the man, who did not want to be named. Sea stars and star fish that he could once see from the beach 30 years ago have all gone, and the papaya he grows in his family’s farm patch are much smaller than they once were, which he attributes to pollution from the power station.

In response to questions about the impact of the plant on biodiversity, Hongkong Electric said that it sends scuba teams to take water and seabed sediment samples from the coastline around the power station on a regular basis. These samples “confirm that marine life has not been affected by the power station’s operations,” it said.

The company also tests leaf litter around the site for signs of contamination and invented a fish deterrent system that uses whale calls to limit the amount of fish that get stuck in its water intake system.

A lone wind farm to keep the lights on

Lamma Power Station may not have kept on burning for 43 years if cleaner alternatives had been deployed to power Hong Kong, industry observers say.

The territory has ample wind energy potential. A study in 2019 found that offshore wind could potentially generate one third of the city’s electricity. A plan to install a 600-hectare, 150-MW wind farm four kilometres southwest of Lamma emerged in 2022 that was supposed to be commissioned by 2027. The farm could generate about four per cent of Hongkong Electric’s electrical output.

An artist’s impression of the planned offshore wind farm 4 kilometres from Lamma Island. Image: Hongkong Electric

But the project appears to have stalled. Things have gone quiet on the wind farm front, said Wheelband.

Hongkong Electric told Eco-Business that the project “remains under discussion with the government” and provided no further updates. This is the second wind farm project to be shelved in Hong Kong in three years. An offshore wind farm east of Clear Water Bay was postponed indefinitely in 2023, with cost cited as a reason for the cancellation.

An environmentalist turned investor, who withheld their name, noted that the power sector lobby is strong in Hong Kong, and has pushed back against wind power for as long as he can remember. Wind energy capacity could have been scaled up 20 years ago if the government had heeded the advice of green groups, he says.

But instead of a farm of 19 turbines that could have eliminated 284,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions a year, Lamma has a solitary windmill that was installed as a trial by Hongkong Electric in 2006. It has remained in beta ever since.

Lamma Winds is a 10 minute walk from Lamma Power Station. It provides enough to power for 250 homes a year. Image: Jun Wei Fan/Flickr

Called Lamma Winds, the single wind mill is perched on a hillside in Tai Ling, a 10-minute walk from Lamma Power Station. Built through a partnership with non-profit Friends of the Earth, the turbine has a capacity of 800 kilowatts and generates enough electricity to power 250 homes a year, in ideal conditions. According to Wheelband, it only generates enough electricity to keep the power station lights on.

Signage at the site explains that Hongkong Electric overcame major challenges to build the turbine, including a limited choice of sites, environmental concerns, and transporting the equipment on rugged terrain. The turbine, which took five years to build, aims to promote renewable energy, attract tourists, and reduce the amount of coal burned in Lamma Power Station by 350 tonnes a year, the signage reads.

Wheelband described the installation of Lamma Winds as a “token gesture” that has never fulfilled its potential. “Green groups pressured the power companies to transition to clean energy – and this is what they came up with,” he said.

For others, the lone windmill reflects Hong Kong’s half-hearted embrace of renewable energy. Lord, the journalist who has lived on the island for two decades, noted that Lamma Power Station is visible from the hill on which Lamma Winds stands. “The contrast between the commitment to renewables and fossil fuels is startling,” he said.

Lamma Winds overlooks Lamma Power Station. Hong Kong’s only wind turbine produces 0.022 per cent of the energy of the coal-fired power station. Image: nhigh / Flickr

While the Chinese mainland added 357 gigawatts of wind and solar in 2024 alone – 10 times the additions made by the United States – Hong Kong’s renewable energy additions were negligible. The territory barely generates a single per cent of its energy from renewable sources, while just under a third of the mainland’s energy is clean. Two-thirds of Hong Kong’s power comes from fossil fuels, one third from nuclear.

“Hong Kong used to be China’s most developed city. But it is miles behind the mainland in the energy transition,” the former environmentalist said.

Hong Kong announced a plan in 2021 to increase renewables capacity to 7.5 to 10 per cent of the energy mix by 2035, and 15 per cent by 2050, but observers say the real shift is from coal to natural gas. More nuclear will follow over the next quarter of a century, and a smattering of new renewables – mostly solar – will help Hong Kong achieve its mid-century target.

Fung argues that the Hong Kong government should be more proactive in its push for renewables in a fossil fuels-heavy energy mix. While there may be vested interests pushing back against clean energy, it is in power companies’ interests to diversify to adapt to falling renewables prices and a public that increasingly wants cleaner energy, he said.

But on Lamma, not everyone is excited about clean energy, if it means change. Jess Kwan, who lived on Lamma from 1998 until 2023, and then moved to Newcastle in the UK for political reasons, said Lamma residents have grown used to the power station and appreciate its role supplying energy to Hong Kong.

She is not too keen on the idea that replacing fossil fuels with renewables could rebrand Lamma as a clean energy hub, and bring in more visitors to the island.

Most Lamma-ites prefer Power Station Beach to Hung Shing Yeh beach, which is more crowded and regarded by locals as the island’s main tourist hotspot, Kwan said. A wind farm is good as an energy source, but not for tourism. We don’t need more tourists.”

Lamma Power Station seen from Hung Shing Yeh beach, Lamma’s most popular beach. Image: Robin Hicks / Eco-Business